Campaign Finance & Free Speech

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

The attack on 527's has initiated a very useful political debate. Bush wants to ban 527's, while free speech advocates, and many Democrats, want to preserve them. Of course on the surface this is a phony fight stemming from naked political self-interest: Republicans are getting hammered by liberal 527's, while Democrats need them to level the playing field in the face of tremendous Republican financial advantages.

But there is much more to this debate than partisanship: there is a debate about the nature of free speech and fair elections. One of the more controversial elements of the McCain-Feingold effort was to limit independent political expenditures, and the 527's are clearly an end-run around the ban on soft money. This issue has divided the left. While good government groups like Common Cause are in favor of closing the loophole, a lot of good, smart liberals (like Nathan Newman and Atrios) argue that these 527's are paradigmatic cases of free speech.

In this instance I am siding with the likes of Common Cause. Unfortunately it seems Atrios and others have accepted the logic of the Buckley vs. Valeo decision. This Supreme Court ruling states that while the government may regulate contributions to campaigns, candidates for office may raise and spend unlimited amounts of money as a form of protected speech. I think this ranks as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. Why? Because it equates money with speech. This influences both the public debate and the ability of candidates to run for office. In the first case, we have to remember that the media is private industry with scarce and limited access. If it were public and unlimited (and cheap), I would no objection to Buckley. But it isn't, so this ruling means that in order to have your views heard, you need to be able to write a check, or know someone who can. This distorts the public debate in favor of the wealthy and connected, and establishes the original Golden Rule: he who has the gold makes the rules.

Buckley also creates a de facto wealth test for office. Since candidates can raise and spend as much money as they like, it gives a tremendous advantage to wealthy and connected candidates. In other words, if you are middle class joe running against Bloomberg, you are going to lose.

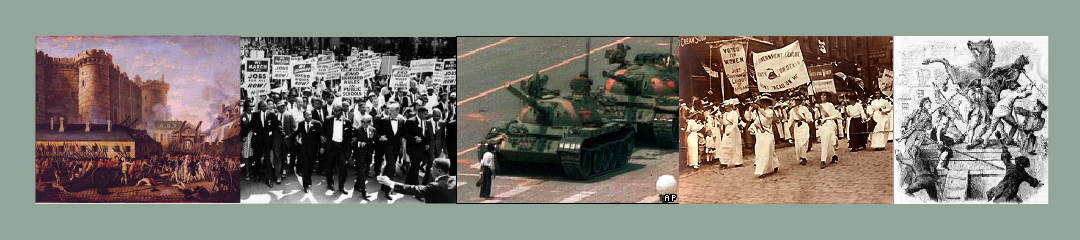

Buckley does not defend democracy, it moves instead to an aristocratic oligarchy. Now of course there are valid free speech considerations. But these need to be addressed in the context of media scarcity and in a way that gives all groups, not just powerful ones, a voice. There are some creative ways to do this- for example, Bruce Ackerman suggests that we give every citizen a 50-dollar voucher to donate anonymously to any political cause they choose. And internet fundraising has certainly broadened the number of people involved and the ability of outsider candidates to run for office. I'm not necessarily endorsing any particular strategy, I'm just saying that there are ways to reconcile free speech and political fairness. And what I want to emphasize is that there is such a tension- we can't just wish it away, or assert that one principle trumps another, which is what the court has done. Free speech without fair elections is argument among oligarchs, while fair elections without free speech is jacobinism. We need to have both.

<$BlogRSDUrl$>

<$BlogRSDUrl$>