Guest Post

Friday, November 05, 2004

I have to go teach but I will continue my election post-mortems later today (trust me, this could go on for weeks). In the meantime, I was sent this interesting little article about the history of the Neocons......TROTSKY AND THE NEOCONS

Benjamin Ross

Was Leon Trotsky the intellectual author of the Iraq War? So argue many anti-war commentators on both the right and the left. They trace the concept of using military intervention as a method of liberation back to the Trotskyist origins of the war’s neoconservative advocates.

Neocons disagree, of course. A lengthy rebuttal by the writer Josh Muravchik in the September 2003 Commentary denies that neoconservatism has Trotskyist roots and sees the focus on Trotsky as a disguised form of anti-Semitism. Debate continues on the internet and in the press.

The argument centers on the neoconservative intellectuals of the 1970s. This was a clearly defined school of thinkers who had indeed started on the left, often with direct or indirect connections to the Trotskyist left. They shifted rightward in response to the cultural radicalism and contempt for democracy of the 1960s New Left, in the process pioneering the anti-elitist stance of today's Republican politicians.

In a 1995 Foreign Affairs article, the liberal writer John Judis contrasted neoconservative foreign policy attitudes with the isolationist and realist schools into which traditional conservatives divided themselves. The neocons’ idealistic interventionism, Judis contended, derived from their Trotskyist background. This provoked a sharp rejoinder from Muravchick, previewing the themes of the current debate.

The neocons who brushed most recently with Trotskyism – and about whom I can speak from personal knowledge -- are a group who began as followers of Max Schachtman. Schachtman had been Trotsky's secretary in the early 1930s and then moved continuously to the right. In the late 1960s he assembled a group of young disciples, several of whom later went on to neocon prominence, and took control of the Young Peoples Socialist League, the youth wing of Norman Thomas's Socialist Party.

I came into contact with this group as a college freshman at the end of 1967. Fiercely opposed to the New Left, and with their position on Vietnam evolving from negotiated settlement to outright support for the war, they had already reached a position on the right wing of any imaginable socialist movement. Yet they still professed to follow Marxism as a systematic doctrine, and their theorizing relied on Schachtman’s Leninist heritage more than European social democracy.

A terminological residue, at the least, remained of the Trotskyist schema in which Stalin destroyed the true communism established under Lenin; there was no doubt what the main enemy was, but it was called Stalinism or totalitarianism rather than Communism. The minutes of the 1969 YPSL convention record that Josh Muravchik rose to amend the Vietnam resolution by substituting “totalitarian” for “Communist” in the sentence “If the war ends in a military victory of one side or the other, the result will be the establishment of a reactionary or a Communist dictatorship.”

An organizational style also persisted from Schachtman's past. This is not a detail; history teaches us that Leninist structures tend toward authoritarianism no matter the doctrines they profess. While the YPSL rejected Lenin's doctrine of democratic centralism, it retained many habits that derived from that doctrine. Schachtman himself, although he usually stayed in the background, was still the insiders’ charismatic leader. And his disciples were not building a typical American voluntary association, with an active core surrounded by a larger number of dues payers. Their aim was to develop a disciplined body of full time militants, who were still called “cadres.”

In 1971 Michael Harrington, then Chairman of the Socialist Party, broke with the Schachtman group. Before leaving the party and founding what became the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, he formed an opposition caucus. Harrington's main issue was Vietnam, but organization was also in question. In an “Open Letter to the Socialist Party,” Harrington charged his opponents with a quasi-Leninist “attempt to transform the Socialist Party into a cadre party.” The point was made by quoting a position paper co-authored by Penn Kemble, later a prominent neocon, that called for “the intervention of socialist political forces, cadres, if you will,” in the Democratic party. Harrington did not fail to observe that “The notion of a cadre party derives in large measure from the Leninist tradition.”

Schachtman and his disciples in the YPSL of the late 1960s were not Trotskyists. They had rejected many of Trotsky's key doctrines and were headed toward neoconservatism. But their travels toward that destination took a tortuous route -- Kemble wanted his socialist cadres to ally themselves with George Meany, Henry Jackson, and other supporters of the Vietnam War. And such intentions were fulfilled; when 1970s neoconservatism coalesced from a school of thought into a committee for this or that, it was usually at the initiative of the Schachtman group.

The formal structures of Schachtmanism itself soon withered, turning by the late 1970s into discussion clubs where newly minted economic conservatives kept in touch with erstwhile comrades who remained loyal to labor. Nonetheless, those who journeyed on to the right retained Trotskyist habits of thought and action. John Judis was correct in 1995 when he brought the connection to general attention. Indeed, neocon guru Norman Podhoretz has made the same point.

How relevant is this to the current debate over war in Iraq? In one narrow respect, very much so. It is simply absurd to suggest, as some antiwar commentators have, that support of Israel would motivate a clique of former Schachtmanites to want to invade Iraq. As Marxists, Schachtman's young followers were non-religious and (despite much political coalition-building with ethnic organizations) saw themselves as internationalists. Support of Israel was the consequence of their political outlook, not the cause of it, and the group was conspicuously indifferent to what is now called Jewish continuity. The anti-Vietnam War wing of the YPSL, in contrast, included many young Jews with strong religious and cultural identification.

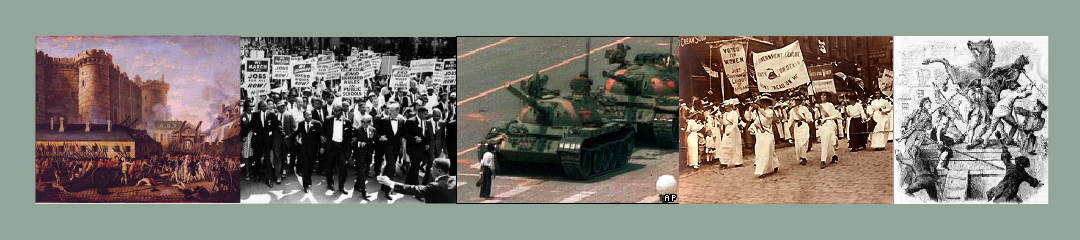

As to the wider issues of Iraq, this history matters far less. To be sure, there are common elements in the foreign policy of the Schachtman group and the idealistic interventionism of today’s neocons. But there is nothing specifically Trotskyist about these ideas. The conviction that democracy is a good thing everywhere is surely shared by many Americans who have never heard of Leon Trotsky. And in spreading a belief system by armed conquest, Trotsky was preceded by Charlemagne, Napoleon, and many others. [You could also add the Girondins during the French Revolution, and, of course, the NAZIs- Publius]

Beyond that, the meaning of the term neoconservative has shifted since the 1970s. Today the word describes all rightist advocates of a strongly interventionist approach to world affairs, regardless of philosophy or past beliefs. Among them the neocons of the 1970s and their successors are only one segment, and at that one whose role is limited to theorizing and advocacy. The men who ordered armies into Iraq are a different group with different backgrounds -- the most scholarly among them, Paul Wolfowitz, is an intellectual heir of the elitist philosopher Leo Strauss.

Still, as the policies that led us into Iraq come to grief, there is at least one striking continuity. Where Marxist theorizing was once used to justify support for the Vietnam War, democratization is now invoked as the rationale for military occupation. Both wars were (in the minds, at least, of their intellectual cheerleaders) fought for grand abstractions. Both were doomed to failure by inconvenient facts their promoters overlooked. The neoconservatives, like Trotsky and Schachtman, were blinded by staring too long at the bright light of the Forces of History.

Hey, that was fun! If anyone else has anything they'd like me to post, just email it to me and I'll take a look at it.

<$BlogRSDUrl$>

<$BlogRSDUrl$>