Campaign Finance & Free Speech

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

The attack on 527's has initiated a very useful political debate. Bush wants to ban 527's, while free speech advocates, and many Democrats, want to preserve them. Of course on the surface this is a phony fight stemming from naked political self-interest: Republicans are getting hammered by liberal 527's, while Democrats need them to level the playing field in the face of tremendous Republican financial advantages.

But there is much more to this debate than partisanship: there is a debate about the nature of free speech and fair elections. One of the more controversial elements of the McCain-Feingold effort was to limit independent political expenditures, and the 527's are clearly an end-run around the ban on soft money. This issue has divided the left. While good government groups like Common Cause are in favor of closing the loophole, a lot of good, smart liberals (like

Nathan Newman and

Atrios) argue that these 527's are paradigmatic cases of free speech.

In this instance I am siding with the likes of Common Cause. Unfortunately it seems Atrios and others have accepted the logic of the Buckley vs. Valeo decision. This Supreme Court ruling states that while the government may regulate contributions to campaigns, candidates for office may raise and spend unlimited amounts of money as a form of protected speech. I think this ranks as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. Why? Because it equates money with speech. This influences both the public debate and the ability of candidates to run for office. In the first case, we have to remember that the media is private industry with scarce and limited access. If it were public and unlimited (and cheap), I would no objection to Buckley. But it isn't, so this ruling means that in order to have your views heard, you need to be able to write a check, or know someone who can. This distorts the public debate in favor of the wealthy and connected, and establishes the original Golden Rule: he who has the gold makes the rules.

Buckley also creates a de facto wealth test for office. Since candidates can raise and spend as much money as they like, it gives a tremendous advantage to wealthy and connected candidates. In other words, if you are middle class joe running against Bloomberg, you are going to lose.

Buckley does not defend democracy, it moves instead to an aristocratic oligarchy. Now of course there are valid free speech considerations. But these need to be addressed in the context of media scarcity and in a way that gives all groups, not just powerful ones, a voice. There are some creative ways to do this- for example,

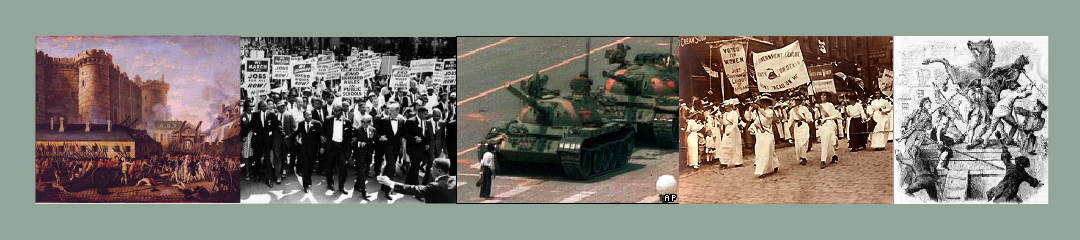

Bruce Ackerman suggests that we give every citizen a 50-dollar voucher to donate anonymously to any political cause they choose. And internet fundraising has certainly broadened the number of people involved and the ability of outsider candidates to run for office. I'm not necessarily endorsing any particular strategy, I'm just saying that there are ways to reconcile free speech and political fairness. And what I want to emphasize is that there is such a tension- we can't just wish it away, or assert that one principle trumps another, which is what the court has done. Free speech without fair elections is argument among oligarchs, while fair elections without free speech is jacobinism. We need to have both.

Back to work

Monday, August 30, 2004

It is very nice to be home. We got back from Italy after a 24-hour travel marathon. It was a great deal of fun, but I missed my cats. And I also felt guilty about not being able to post here every day.

There are a few things floating around the internet while I waa gone that I want to talk about. One is the proposal to move to an instant run-off voting system (see

here). I've spoken at length about the the wisdom of moving towards a multi-party system, which would be the effect of such a system (see my May 29 post in the Archives for the full discussion). An excerpt what I wrote on this subject:

The second Nader argument is that we should scrap the 2-party system and move to a genuine multiparty system like in Europe. This is only going to happen if we changed the electoral structure to a multi-member district proportional representation system. We could do this, of course- all it would take is change in state and federal law. The way we do it now is not in the constitution. So the 2 major parties would disaggregate into their constituent elements. You would have christian, corporate and libertarian parties on the right, and civil liberties, environmental, and labor parties on the left.

This is a really, really bad idea. Anyone who has taken PoliSci 101 knows about how the separation of powers and checks and balances make it almost impossible to pass legislation. One of the few things that help you overcome gridlock is unified party control. What would happen if you overlaid a multiparty system on top of our legislative structure? People should know that Europe has basically unicameral systems, so the checks and balances work themselves out when parties form coalitions after the election. So we would be adding ANOTHER layer of checks and balances onto an already unwieldly system. And you know what? This would just benefit the right, not the left, since they right is full of people who are already benefiting from the current social arrangements, and it would be easier for them to play us off against each other. So to really go multi-party, you'd have to abolish the Presidency and the Senate. Good luck with that.

Finally, 3rd parties are just unnecessary. In one sense, we already have a multi-party system. Both parties are coalitions of what would be separate parties in Europe. In Europe, the ally after the elections. And it's almost always coalitions of the right or left, just like here. Here we do it before the elections and on a more permanent basis, giving the alliance a brand name. You would still have give and take between factions over policy, so I'm not sure what you'd gain. Also, the voters would have to vote for a party rather than a person, which they may not like doing.

Finally, if someone does have a distinct position they are pushing, it makes more sense to mobilize within one of the two pre-existing parties. You can contest primaries and maybe get your faction the nomination. Even if you lose, if you do well enough the nominee will have to meet you part of the way. And a faction gains tons of influence when they deliver votes and activists. Just look at the labor movement or the religious conservatives. They could have formed their own parties, but they took the smarter path and now have tremendous influence within the major parties. If Nader had been serious, he would have challenged Gore or Kerry in the primaries and then he would have had credibility for himself and his movement. But I don't think Nader is serious.

So if you are in Detroit, vote against the resolution!

The second issue I want to discuss is the electoral college. The

New York Times Editorial Board has trotted out the idea of abolishing it, to be replaced by direct popular vote. The column lays out all the sins of the EC: that is violates the one man/one vote standard (by over-representing small states), disenfrachises voters (if they don't live in swing states), and can result in undemocratic outcomes (where the popular vote winner loses the EC).

But the NYT approach is superficial and unsystematic. They fail to diagnose the sources of these problems, or carefully evaluate the alternatives. I'll try and do better. The difficulties with the EC stem from two institutional features: the winner-take-all allocation of electoral college votes, which is a product of state law, and the over-representation of small states, which is part of the Constitution. The former feature makes for the swing-state phenomenon, the latter the bonus for rural voters, and they combine to make it possible for a popular vote loser to be elected.

The NYT proposal to move to a direct popular vote seems to address both problems, but it creates new ones and ignores a major difficulty. Abolishing the college would mean that re-counts would have to be nation-wide (think Florida for the whole country), and would undermine the two-party system (see above). But the insuperable difficulty is that getting rid of the electoral college is impossible. Small states would have to ratify any constitutional amendment, which would be against their self-interest. So forget about it- it is NEVER going to happen. The small-state bonus is here to stay.

But we can tackle the winner-take-all feature, since it would only take a change in state law. A truly terrible idea is the Maine-Nebraska plan, which allocates electoral college votes by congressional district. Because of gerrymandering, this proposal would make it more likely that the national popular vote winner would lose. If this system had been in place in 1976, Gerald Ford would have won even though Carter won the national vote by 2 percentage points.

Colorado is considering another proposal. In that state, a referendum is on the ballot to allocate electoral votes by the candidate's proportion of the vote. So if Bush wins 51-49, then he gets 5 votes rather than 4. This would eliminate the winner-take-all problem, and if a threshold was added, it would preserve the 2-party system. Unfortunately, eliminating the winner-take-all feature would

strengthen the influence of small states. I conducted an analysis of 2000 and discovered (much to my surprise) that George Bush would have been elected under this system.

So what do we do? I'm really not sure. The best combination might be to move to the Colorado plan nationwide while adopting Schlesinger's proposal for a constitutional amendment which would give the popular vote winner a bonus in the Electoral College. This would be a roundabout way of neutralizing that small state advantage, but it might be easier to convince the small states of because it would explicitly address the real concern with the electoral college: that the national popular vote winner might lose. But I don't think the prospects even for this change are realistic. It is most likely that we are stuck with the system we have. Which means that Democrats need to work to overcome their disadvantage in rural areas- otherwise the Electoral College and the Senate will continue to be gerrymandered in favor of Republicans.

Thoughts on Italy

Monday, August 23, 2004

If my syntax is a bit strange at times, or there are typos, it is probably because European keyboards a different from American ones. What can you do.

This is my first trip to Europe, so I will avoid comparisons with any other country on the Continent. This is a remarkably beautiful and well-ordered country with an absurd number of historical monuments. So far I have seen Rome, Naples, Florence and Turin. Each has been profoundly different, at least from what I can tell in very brief stays. I must confess that I have only hit the major tourist traps at each locale, so I can't claim any deep knowledge. But a week in which you can see St Peter's, the Vatican, the Forum, a fifth-century neighborhood, Brunelleschi's dome, the Uffezi, and the FIAT building (okay, so Turin isn't as nice) can be described as a very pleasant time.

I won't bore you with a list of monuments- they're in every art history book. I will tell you that this is a very easy (although expensive) place to be a tourist. In most of the principal towns a smattering of Italian will do, and the mass transit system only reinforces my suspicions about the U.S. transportation system. The food is good too (duh).

Politically, I don't have much to say. There has been a lot of attention devoted to the Olympics, of course. They are also very interested in Iraq- the recent Najaf events dominated the news for days. My brief scanning of U.S. papers saw a comparable amount of attention of the swiftboat stuff. Can someone please explain what is going on at home? On the whole there is no visceral anti-American sentiment, which is nice. But I can expect what would happen if I were to engage in a conversation starting with "So what do you think of Bush?" Actually, if I get the chance, I think I'll do just that. As long as my wife isn't looking.

Ciao.

P.S. Italian coffee tastes like turpentine.

Italy

Sunday, August 22, 2004

This is my first access to the internet since I have arrived in Italy. I do not have time to talk, but I will write more tomorow. It is lovely here. Anyone who has not seen Florence or Rome is really missing out.

Comments

Monday, August 16, 2004

There are a lot of things that need responding to this morning:

1)

Matt Yglesias and

George Will both misunderstand Alexander Hamilton- he was neither a pure mercantilist nor a pure free trader. The "infant industries" argument is that you protect new manufacturing, but once it is competitive you leave it open to (fair) international competition. This is why he favored subsidies over tariffs. Oh, and you always protect industries with military applications- you don't want to rely on another country to produce your tanks. But there is a cottage industry misunderstanding Hamilton, so why should I be surprised?

2)

The Washington Post continues its march to the right again today. They seem to believe that the only thing wrong with the Bush tax cuts are the deficits they create- everything would be great if only he would cut spending! Except we should increase social investment spending. And tort reform is a big problem. What is wrong with these people? When did they drink the conservative kool-aid (you know, Jim Jones)?

3) Yet another

election forecasting model that overestimates the role of economics in elections, and only GDP and inflation numbers at that. Bush is NOT going to win by 58%. Didn't they learn in 2000?

4)

Joel Rogers at the Nation has a great article about the importance of liberal organization at the state and local level. I've posted on this issue myself, and I am glad that others are thinking along the same lines.

One more thing. I am going to Italy for two weeks, so my posting will be intermittent, particularly this week. But I do hope to be able to comment on European reaction to the U.S. politics.

A Roma!

Meritocracy

Sunday, August 15, 2004

There is an old curse: may you get what you deserve. What we deserve is a matter of intense dispute among political philosophers and commentators alike.

Will Wilkinson has recently argued that effort matters- we deserve what we do.

Matt Yglesias and

Matt Miller, on the other hand, claim that human desert is very contingent.

First I want to make clear that Yglesias and Miller have staked out a very questionable position, one that few political theorists on the left have embraced- that people deserve nothing because their character (and effort) are themselves a product of undeserved chance. And Wilkinson has misrepresented Rawls's position. Wilkinson selectively quotes from A Theory of Justice to the effect that Rawls thinks that natural endowments are arbitrary. What he fails to note that is that Rawls believes that the basic institutions of society should not

reinforce these inequalities, not that the state should actively intervene to rectify social imbalances.

If we reject the extreme "redistributionist" arguments (which most egalitarian theorists do), then we are left to refute the extreme libertarian ones. Wilkinson follows along with Nozick that people's effort (and reward) are their exclusive property right, and it therefore violates the autonomy of the person to take the fruits of their labors to help someone less fortunate (whatever the reason for that misfortune).

Of course this theory presumes that the market is a just procedure, when even a cursory examination of the market mechanism is that it is a) arbitrary and b) frequently unjust. For example, Michael Jordan is one of the world's wealthiest men, but would he have been with the continuance of slavery or before the invention of basketball? Probably not.

The market is not the product of natural laws: it is the product of social regulation. The existence of the market is an artifact of public policy- modern corporations were created with a change in contract law in the 19th century. Entrepreneurs' success would be impossible without the conditions created by the efforts of government to guarantee opportunities, social order, a free and competitive market, etc.

So where does that leave us? Probably where we should be- with a belief that people deserve

some of the fruits of their labors, but not

all, because we recognize that a good portion of our success is due to chance and to the efforts of others.

A just society should fairly distribute the social product. In other words, we are all in this together. It is manifestly unfair if everyone works hard but only a few people benefit. It is also unfair if some people contribute more than others but get nothing extra for it. The trick is to strike the right balance.

Unfortunately, today we are very far from achieving that happy equilibrium. Reaching it is not made any easier when liberals like Miller and Yglesias make specious arguments. But their hearts are at least in the right place. Conservatives seem to lack any notion of reciprocity at all. But that is very old news.

The Ownership Society

Saturday, August 14, 2004

Will wonders never cease. President Bush has recently enunciated a coherent intellectual position: that the U.S. should become an "ownership society" in which all have a concrete stake and reward in political outcomes. We should move away from socialized and towards personal risk while structuring rewards based on individual effort.

This theory is very much in line with the "investor class" discussion on the right: that the entry of the middle class into the stock market will inculcate conservative political values in main street America. Republicans believe that the New Economy will result in a conservative political realignment once enough people are invested in the market. They will reject "socialism" (read: liberalism) in favor of an entrepreneurial ethic.

Paul Krugman has rightly criticized this idea as a smokescreen for shifting (yet more) economic and political power to the very rich. Krugman notes that while a majority of Americans are now invested in the stock market, the vast preponderance of assets in the market are still in the hands of the the top 10% (don't quote me, but I think their share is something like 90%).

When I read Krugman's op-ed, I nodded up and down and thought that would be the end of it. But some conservatives just won't letter the matter drop.

Here is one column critiquing Krugman's post and lauding the virtues of the Ownership Society. In his piece, the Judd argues the following:

We should, of course, return to a system where only those who actually pay taxes and have vested property interests in the state are entitled to determine how their tax dollars are spent, but Mr. Krugman, as most of the President's critics, dramatically underestimates how radical a transformation he envisions. The ownership society would make it so that everyone falls under that rubric--this is its conservative genius. The classic conservative critique of democracy is that a system which allows the majority to vote itself the money of the minority will eventually see exactly that happen. But, by transitioning from income to consumption taxes you make sure that even the poorer among us feel the pinch of too high government spending and give them a reason to oppose it. By creating personal property for them to own--in the form of Health Savings Accounts; privatized Social Security Accounts; private instead of public housing; etc.--you give them a vested interest in the stability of the society and in the growth of the economy. The ambition may be sane, but it is too make every man an elite, an owner of a personal stake in the nation.

Additionally, and it's even more surprising that Mr. Krugman doesn't get this, the ownership society is a way of getting out hands of government, where it at best lies fallow, and into the hands of the productive economy. Here's how Daniel Altman explains their vision:

[They] postulate the following chain reaction:

1. Government cuts tax rates on savings and wealth.

2. Saving by households—bank accounts, stocks, bonds, etc.—increases.

3. More money becomes available to American businesses, since they're the ones offering the bank accounts, stocks, bonds, etc.

4. Businesses spend more on machinery, software, and other capital, as well as on research and development.

5. The nation's output of goods and services grows, and technological innovation accelerates.

6. Incomes and living standards rise more quickly for several years and perhaps forever.

Sending a trillion dollars back to the wealthy in tax cuts is all well and good, but the big enchilada is obviously the enormous pool of Social Security money--real and imagined. Rather than having the government collect Social Security taxes and sit on them a prtivatized system would put tens of trillions of dollars into stocks and bonds. The increased return on those dollars is reason enough to make this change but the neoconomists believe that making all this additional money available to business will increase the rate at which the economy can grow.

That may be delusional, but if so Mr. Krugman, who folks swear was a respected economist just a few years ago, isn't offering any reasons why it is. Indeed, his argument seems to be based almost entirely on the Left's political desire to keep folks poor and atomized so that they will support redistribution of wealth. That's a sensible plan for the elites who want to run the redistribution and control lives, but it's bad for the country, including the poor.

I want to highlight the first sentence, because it is shocking:

"We should, of course, return to a system where only those who actually pay taxes and have vested property interests in the state are entitled to determine how their tax dollars are spent...." What are we to make of this? Just that the writer begins by bolding suggesting that the wealthy in society should have more political power than the poor. Under his principle, there are only two choices: either we have a simple flat head tax (which would shift a massive tax burden onto the poor and middle class) or the rich should have more political influence (which will result in a dimunition of power for the poor and middle class). This is an argument no one has made since we did away with property qualifications for voting in the 1820's!

Judd doesn't stop there. He goes on to reveal that the ownership society is a device for getting the middle class to oppose government. By shifting the tax burden onto the lucky duckies (and cutting social services they expect), the broad mass of people will decide government is their enemy.

Why is this a good thing? Why, because the dimunition of government will result in economic growth, of course. Judd cites the basic supply-side argument that putting wealth into the hands of the elite will enable them to use it most efficiently, generating growth that will raise middle incomes.

Of course, this theory is just silly, because it presumes that a) elite wealth leads to economic growth, and b) that aggregate growth results in higher middle incomes. These two points are at the very center of today's economic debate. It also ignores the global economy, which enables this elite to invest

somewhere else.

But I will leave the economics discussion to the economists. What is most enlightening is Judd's contempt for the democratic process. He not only wants to manipulate the debate so we can move to his preferred outcome, but reveals the essential conservative discomfort with democracy itself: "The classic conservative critique of democracy is that a system which allows the majority to vote itself the money of the minority will eventually see exactly that happen."

So what have we learned about conservatives? At their best they are fools, and worst they are tyrants. They either a) confuse the interests of the wealthy and the nation, or b) don't trust democracy and will abuse it to get their way.

At least now we know what we're up against.

The Republican National Convention

Friday, August 13, 2004

Will the Republican Convention help Bush or not?

There is an expectation that massive protests will occur in New York during the Republican National Convention. Some people are concerned that these protests could actually help Bush, particularly if the media covers a lot of wack job anarchists and/or there is violence. But I am of the mind that the media will cover the crazies no matter how few they are- if the only protesters are nut jobs, then that will be all that is covered. However, if there are a million people in the streets of all shapes and sizes, maybe the wierdos will get less attention. And I think that violence might be less likely with huge crowds than with moderate-sized ones. We'll see.

I believe that the overall situation is dicey for the Republicans. First of all, the networks aren't going to show the McCain and Guiliani speeches, which are the most important for Bush because they present the moderate face of the party. And second, if they appear to be trying to capitalize on 9/11, they are risking a backlash. Remember the response to Bush's first set of ads?

So I think that there are three likely scenarios, mentioned in order of probability. The first is that there is a moderately successful convention in which Bush enjoys a slight bounce. The second is that it is a failed convention as swing voters become disgusted with the politicization of 9/11. The third is that that the protesters make Bush look like a strong leader and alienate middle america.

So which of the three do you think is most likely? Or is there another option I haven't considered?

The Honesty Issue

Thursday, August 12, 2004

The right wing blogs are in a tizzy over Kerry's statements about Cambodia- check out

Instapundit and

Pardon My English for some examples. Now I'll leave it to the professional journalist types to knock this line of argument down. But I would like to point out what this campaign says about the Republicans. They've got nothing. No issues. No real attacks- just feeble efforts at character assassination. This campaign is even nastier and has less content than the last Bush campaign (or the one before that, or the one before that, or....).

What I'm curious about is whether the media will pick up the story. Given how they handled the "intern" flap, it wouldn't surprise me. Stay tuned.

Debating Economics

Wednesday, August 11, 2004

The economic debate has become very sterile over the last two decades. With the Keynesian consensus of the postwar era in collapse by 1980, the parties staked out very different visions. They have stuck to those visions every since, with only minor modifications.

Republicans argue that growth is best achieved by maximizing the rewards and minimizing the costs to entrepreneurs- eventually everyone will benefit. Oh, and deficits don't matter. Economic stimulus is best done, therefore, by cutting taxes on upper-income individuals.

Democrats counter-argue that instead we should maximize the purchasing power of middle and working class consumers in order to stimulate demand. This way there is someone to buy the products the entrepreneurs are selling, as well as guarantee a fair distribution of benefits. Large deficits are bad- if you reduce them, you can use low interest rates to stimulate the economy.

On the surface this dispute seems like a reasonable debate on how best to achieve growth. But the underlying assumptions of both are flawed, and the overall orientation is misdirected. Both sides have only a superficial emphasis on growth. In reality, what we have is a fight over distribution- who gets what share of the pie. Each party is championing the interests of its constituency at the expense of the other.

So what's the problem with that? Well, you can't cut up the pie if the pie is shrinking. Neither party's strategy for growth is adequate, because both Keynesianism and Neoclassical economics essentially assumes a closed economy. But as everyone knows, we now live in an increasingly globalized economy. So entrepreneurs, if they invest or create jobs, can do so overseas rather than in the U.S. And consumers aren't necessarily buying products made here. So the bang for the buck on fiscal stimulus is quite a bit less than it used to be. And monetary policy has reached its limits because we now have massive corporate and private indebteness (and a massive public debt to boot).

This stalemate has had grievous political consequences, both for the left and the country. The left has been caught in a bidding war with Republicans over who can cut taxes more- a debate we will never win. All we can do is whine "that's not fair!" Not that persuasive. Meanwhile, declining U.S. competitiveness and the erosion of the middle class continues unabated.

So how do we break out of this party and national dilemma? Well, I've been reading Michael Holt's book on the old Whig Party, and it struck me that the economic debates of the 19th century were only partly distributional. The Democrats were the anti-statist party: they wanted government to stay out of economic development (because they feared government action would be to the benefit of the wealthy), and the Whigs (most of whom later became Republicans) argued that national action could develop the nation's resources. They had a comprehensive plan (borrowed from Hamilton) to encourage growth. And guess who had the more compelling economic message? You might be surprised, but it was the WHIGS, not the Dem's. Anti-statism, when confronted with specific problems rather than abstract commitments, tends to be fairly unpopular.

So the Democrats should shift away from a debate strictly about distribution, and should focus on growth. We should articulate a vision of how liberal economic policies can benefit the middle class and the nation at large in the context of a global economy. As usual, Clinton pointed the way here, with his talk about human capital development and pro-labor, pro-environment trade policies. But we need to think harder about how to do so, and then how to pitch the idea to people.

If you provide a clear idea of how you intend to use government, then you can generate support for it. This will force the right to bash specific (and popular) programs, rathen than giving them the easy target of "big government." The Republicans took over the Whig's strategy in the 1860's, and it had not a little to do with their 70 year political majority.

Interesting Articles

Tuesday, August 10, 2004

The Washington Post has an op-ed on the vulnerable position of the middle class by

Jacob Hacker. Although he doesn't suggest any real specifics on how to enhance middle class security, he does lay out the general problem quite well. I think that debt and health care, as well as our continuing neglect of child care, remain the key issues.

And my response to this

article should restore my humanitarian credentials after what I said yesterday. Asking people their immigrant status before giving them medical care is obscene. Of course the administration is claiming that they are just making sure money is spent properly. Poppycock. This provision will discourage people from going to a doctor, and that is simply wrong. I hate cliches, but this is a good one: health care is a right, not a privilege. We help people live because they are fellow human beings- our duties as people outwiegh the narrower obligations of citizenship.

People shouldn't die unnecessarily. Why do some people find that concept so hard to grasp?

Immigrants & the Vote

Monday, August 09, 2004

I have generally stayed away from the issue of immigration. Not because I don't have opinions, but because, like gun control or abortion, emotions run so high it is almost impossible to have a rational discussion. But this NYT

article deserves some commentary. Apparently there is an effort underway do give the all residents of a city the right to vote. Whether they are citizens or not, legal immigrants or illegal.

I think this a truly awful idea. It comes from admirable humanitarian impulses, but it is fundamentally wrongheaded. Citizenship is essentially tied up with the right to vote. You cannot separate the two. Voting is an act of communal self-government, and as such participants must be members in good standing of the political community.

So why not just grant citizenship to all residents? After all, they contribute to the economy and civic life, so they should have an appropriate share of the burdens and responsibilities of citizenship. I think this argument confuses the nature of citizenship. Citizenship is not merely an economic contract. As Aristotle argues in the Politics, members of a community are not merely cooperating in a common economic and social enterprise, they are members of a community with shared moral principles. Political communities are about something- they have core animating principles that motivate their members.

Let me give you a concrete example. If France adopted the U.S. Constitution and U.S. laws, would they suddenly become indistinguishable from America? Of course not- they have a very distinct history, cultural, and set of values. They are a different people.

Now some might argue that the United States is not a homogenous cultural unit like France. I think this is a common misconception. Communities are not defined by their ethnic composition but by their communal principles. Both France and the U.S. are ethnically diverse populations, if you go back far enough. The U.S. is somewhat more adaptable in its culture, but the difference is one of degree, not kind. But if someone with French grandparents were to visit Paris, he would realize how American he or she really is.

So by all means, work to protect the economic and social interests of immigrants. But don't confuse their contributions to a society with membership in that society.

Terror Terror Everywhere...

Sunday, August 08, 2004

So with the economy tanking, Iraq going up in flames, a Presidential campaign underway, what does the media cover?

Why, the War on Terror, of course. Which just HAPPENS to be the only issue that Bush leads Kerry on. And by sheer coincidence there is a 1 to 1 correlation between Bush's approval numbers and new terror alerts.

Sigh. Sometimes it's hard being a critic of conspiracy theories.

Would Someone Please Explain James Pinkerton To Me

Saturday, August 07, 2004

In an editorial in Newsday,

Pinkerton suggests that the Democrats are using concerns about Diebold to divert attention from their own plan to steal votes. His evidence? That everybody knows Daly's Chicago machine stole the election in 1960.

This argument is just bizarre. An event which may or may not have happened (whatever Pinkerton claims) nearly half a century ago is supposed to prove more revealing than the undisputed actions of the last four years? What kind of logic is this?

For your edification, let's look at the recent evidence of monkeying with the vote by both parties. Then we will evaluate who should be under greater suspicion for trying to subvert the democratic process.

Republicans:

1) Advertising the wrong election dates in black neighborhoods

2) Sending bogus letters to blacks that they have to have their rent paid before they vote.

3) Surrounding polling places with armed guards, which will intimidate voters

4) Striking blacks off the voting rolls, falsely claiming they are "felons"

5) Opposing a paper trail for computerized voting machines, thus preventing a real recount.

6) Sponsoring the use of machines by a company which is a contributor to the Republican party.

Democrats:

That seems to clear the matter up, don't you think?

Gay Marriage: The Revenge

Friday, August 06, 2004

It looks like the gay marriage issue might be returning to the political headlines. Last Tuesday's primary in Missouri resulted in overwhelming support for a state constitutional ban, with unusually high turnout. Some of that voter participation might have been due to the Democratic primary's competitiveness (the incumbent Governor was unseated!), but not all of it.

The concern is this: the gay marriage issue might bring lots of Republicans to the polls, and cost us dearly among the working class whites that are crucial to Kerry's election. I think this is a potentially big problem and requires some real thought. But it may not be as large a problem as we suspect.

There are two issues at stake: increased Republican turnout, and the defection of Democratic and swing voters. First to the issue of turnout: it is quite possible that gay marriage motivated a large number of voters to show up at the primary. But you need to remember that these are habitual voters- they are people who are likely to vote in the Presidential election. It is a far easier to task to get habitual voters to participate in a primary than get non-voters to participate in a general election. So I think this concern is over-stated.

I am not worried at all about the defection of Democrats. I suspect that the vote for the ban was driven in part by african-american ballots. They may be on Bush's side on THIS issue, but I doubt that gay marriage is of such salience to cause the loss of core Democratic supporters.

The real risk, then, is the swing vote. And here we might have a legitimate problem. Democrats cannot win the election without being competitive among white working class voters. Gore's failure here is what cost him Missouri last time. So the question is whether gay marriage will be an issue of sufficient power to overshadow the economic and foreign policy blunders of the Bush administration. This simply gets us back where we started- Republicans have to change the subject to cultural issues, or the war on terrorism, or they will be defeated.

Kerry's strategy on this issue is a good one. He is not talking about the issue, which is precisely the correct move. To address it is to raise the issue profile of gay marriage, which is what we don't want to do. He also has a clever position: he is opposed to a constitutional amendment and thinks it should be left up the states, even while personally rejecting gay marriage and supporting civil unions.

Which I think is where the majority of the American people are.

Celebrities

Thursday, August 05, 2004

The prominence of Ben Affleck on the campaign trail and the newly announced rock stars for change tour (Springsteen, REM, etc., etc.) has got me thinking about the role that celebrities are playing in the Democratic party, and politics generally. Clearly I would prefer it if celebrity didn't matter, but regrettably it does. We live in a society obsessed with fame, with movie stars talking politics and politicians treated like movie stars. What is interesting is that the majority of artists are on the left, and have been throughout this century. This phenomenon is due to a number of factors: the social liberalism of the arts, the dislike of tradition and authority, the generally low esteem in which artists have been held (they are feted even while they are loathed).

But how does this pro-Democratic alignment affect liberal prospects? While they do provide a certain glitz, attracting larger crowds and more media attention, the open participation of Hollywood in Democratic politics is probably a net minus. The right works furiously to divert populist anger from corporations and the rich to any other subject. One of their handiest weapons has been the "cultural elitism" of Democrats. Working class people envy and disapprove of movie and rock stars even while they worship them. By giving them such a prominent position in liberal politics, we make it far easier for conservatives to claim we are out of touch with mainstream values. It isn't fair, but that has never really mattered to our opponents.

I don't think we need to lock Rob Reiner and Glenn Close in the basement. I just think we need to get off the Convention stage.

Until the movie stars are running for office, that is.

P.S. Site Meter has just been added to this page, so I'll finally get some idea of how many people are reading my blog. Here's hoping!

The Wife Issue

Wednesday, August 04, 2004

It is truly disturbing the depths to which modern (Republican) campaigning has sunk. First it was Kitty Dukakis' substance abuse problems, then Hilary for not being feminine enough, now there is a similar assault on Teresa. Why is it that the right is so quick to attack an opponent's spouse?

I think that Republicans are trying to use the Dem's wives to send a symbolic message about the candidate, and even the party as a whole. First of all, one of their target groups is working class women with children. If the prospective first lady can be painted as contemptuous of "family values," it reinforces the social wedge issue (do you remember the Tammy Wynette flap?). It also can be used to pursue the "liberal elitist" line. This is why Hilary's professionalism and Teresa's wealth and outspoken behavior have been hyped by the Republicans. It allows conservatives to paint the Democrats as looking down on middle income traditionalist mothers.

The other advantage of the wife issue is the latent belief that a strong wife makes for a weak husband. This is absurd, of course- marriage is not a zero sum game. In fact, I would suggest that any man who deliberately chose a forceful wife should be commended for his own strength (truth in advertising- I married to strong woman myself). Only weaklings wanted to be surrounded by weaklings. But this is not what most of the population believes, so if Teresa, Hilary, and whoever are prominent in the campaign, then it only reinforces the perception of the Democratic nominee as lacking in strength.

These are all despicable maneuvers, of course. But they do explain why Democratic campaign managers have tried to keep the spouses under wraps. If they don't, they not only weaken their candidate but give the right yet another opportunity to play to America's worst and most misguided prejudices.

I think a better strategy would be to highlight the issue. Responding to the attacks is good politics - no one looks stronger than when they are standing up for their family (Clinton did this to great effect during the '92 primaries). I also think it is good policy- if we point to how the Republicans are once again trying to pit one group against the other (professional vs. traditional women), we can not only shut them up but perhaps change some minds.

The Conservative Blog Wasteland

Tuesday, August 03, 2004

I had a couple of ideas when I started this blog. One was to use a theoretical and historical prism to analyze political events. It's up to the reader to decide how well I've accomplished that task. But another aim was to rebut conservative arguments, particularly on right-wing (or at least anti-Kerry) blogs. I haven't been permitted to do much of that, because they really haven't had much to say.

Let me give you some examples of their most recent posts. My comments are in parentheses.

Kaus: Kerry is a flip-flopper because he has criticized the No Child Left Behind Act. (Of course, what he has criticized is the lack of funding and its implementation, not the idea itself)

Pardon My English: The 9/11 commission didn't blame Bush. (With half Republicans, did you really think they would? And did you notice that the Iraq stuff has been delayed until after November?) The writer then goes on to claim the Clinton Admin punted on terrorism (while in reality a good part of the 2nd term was focused on it) and then attempts to explain why they punted (when he hasn't even proved point one). Apparently Clinton hates the military and intelligence. (Interesting, given the thoroughgoing reform of the military during the 90's.)

Another writer on that blog claimed that Kerry "lied" in his speech about strengthening our relationship with our allies in that "only people who aren't on our side are theones who want to see us fail." (Is he talking about the War on Terror or Iraq? Because if so both points are incorrect, if you read public statements by european governments. And does "our side" refer to George Bush or the U.S.? Because if the former is the case, then he's right, they do hate Bush and want to see him fail.)

Finally, Andrew Sullivan spends a lot of time just commenting on other people's posts or put up the "email of the day." The last time he wrote was to criticize the Kerry speech as too long, arrogant, condescending. He thought the joke about being born in the west wing of the hospital was the comment of a "jerk." (Was he aware that this was a JOKE. And Laurence O'Donnell made a good point about the length of the Kerry speech- it was designed to be broken up into sound bites. Makes sense, and explains the same scattered character of Clinton's speeches.)

So as you can see, there is a scattershot and fairly weak criticism of Kerry coming out of the right. And this is pretty much par for the course. So I will continue my vain search for a conservative opponent worthy of the name. (Now THAT is an arrogant comment, Mr. Sullivan!)

What does the future hold?

Monday, August 02, 2004

I've been re-reading some of my political analysis books lately- Jeff Faux's "The Party's Not Over," Teixeira's "The Emerging Democratic Majority," and the classic by E.J. Dionne, "Why Americans Hate Politics," as well as his "They Only Look Dead." Reading Thomas Franks' "What's the Matter with Kansas" got me thinking about the broader challenges faced by the Democratic and Republican coalitions over the next couple of decades.

The Democrats are a coalition of cultural and ethnic minorities (gays, feminists, blacks, latinos, etc.), populists (working class laborers), and progressives (animated by social liberalism, the environment, etc.) Traditionally the Democratic Party was defined by its populism, but the progressives won control during the twentieth century. During the 1960's a combination of factors drove a large portion of the populists from the party, which cost liberalism its political majority. They have been struggling to pick up the pieces ever since.

The Republicans, on the other hand, are a combination of libertarians, corporations, cultural traditionalists, and foreign policy nationalists. This is a coalition that was assembled by Nixon and Reagan, but lost its clear majority status in the 1990's because of the end of the cold war, economic anxiety, the rising percentage of minority voters, and increased social tolerance.

So where does that leave us? Well, Teixeira would have us believe that the trends are towards the Democrats, with an increasingly tolerant electorate(due to the growth of ideapolis), the proletarianization of middle class professionals, and the growing minority population. The Republicans (and Franks) would suggest that the drive towards small government, the growth of the sunbelt, and the increasing identification of working class voters with cultural conservativism will guarantee them a new majority.

I think either scenario is equally plausible. There are several key questions, the answers to which will give us a good idea of what is going to happen. Will the Republicans be able to win more of the new immigrant populations? Will they be able to generalize their cultural conservatism beyond protestantism? Will middle class professionals continue to become more interventionist on economics? Will the salience of cultural issues increase or decrease? And which constituency (professionals or the working class) will grow in size?

I think the elephant (or donkey) in the room is the deteriorating position of the middle class in the U.S. Their reaction to the backwash of globalization will determine who has the advantage. If they blame corporate america and global trade, they are likely to become Democrats. But if they blame big government, minorities, and cultural decline, they will become Republicans. Democrats, for the sake of the republic and for their own futures, need to lay out a comprehensive agenda for dealing with the challenges of the New Economy. In short, we need to define for people ahead of time what the problems are and how to deal with them. If we don't, we are just gambling that people will see things our way when the time comes. And that's just too risky.

Sunday Wrap-up

Sunday, August 01, 2004

I wish I had more commentary than I do, but there really wasn't much interesting on this morning. The discussion was focused on Kerry's position now that the convention is over. Of course, with one exception they used Newsweek's flawed poll (Ruy Teixeira demolished it pretty effectively, I thought). Zell Miller continued his long descent into madness on Russert, and Biden did pretty well. On almost every morning show was a Kerry-Edwards interview. Kerry is still not rebutting the 87 billion charge as effectively as he should: he could if he chose successfully re-frame the issue as an attack against Bush. But he did come out and state that Bush broke his word to Congress in the run-up to the Gulf War. And he very cleverly, I thought, brushed off Nixon's "secret plan" strategy for how he would deal with Iraq. Frankly, I never thought that it made any sense to tie yourself down in case you do get elected. If it was good enough for Lincoln, it should be good enough for us.

Hey, is Mary Matalin shrill or what? I thought Donna Brazile made a good counterpoint by exuding sweet reasonableness. I just wish she was more effective at debate.

Overall, the McLaughlin Group had the best analysis of the convention: Kerry and the Democrats performed very well, and Kerry has been greatly strengthened. Now if we can only get through August in one piece.

<$BlogRSDUrl$>

<$BlogRSDUrl$>